Governments around the world are taking extraordinary measures in the fight against COVID-19. Many of these are essential steps to protect health and life. However, some states are enacting laws that dangerously undermine civil and political rights. In this post, we look at the threats to rights arising as a result of emergency legislation ostensibly intended to fight the pandemic.

Emergency laws

Around the world, governments are enacting emergency laws in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of these laws contain powers that could be considered excessive: screening and isolation of certain persons; closing premises and prohibiting events; postponing elections; shutting down courts and delaying trials.

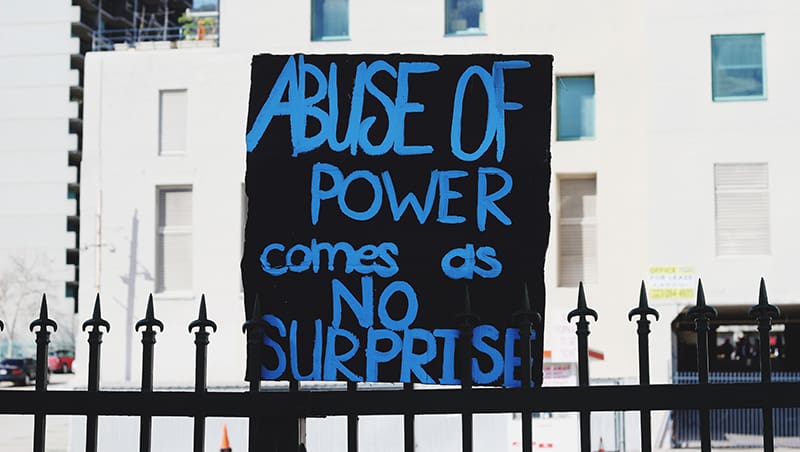

While many of the measures are justified, emergency powers carry an inherent risk of abuse. It is already evident that many governments are using the COVID-19 pandemic to rush through laws that impose disproportionate restrictions on protected rights and freedoms.

Many of these measures share two common features: First, they significantly increase executive power, enabling governments to make decisions without the traditional constraints of democratically elected parliaments. Secondly, they impose restraints on the media, impeding access to information and stifling critical reporting that might provide alternative oversight. For example:

- On 30th March, Hungary’s parliament adopted a draconian emergency law that allows Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to suspend laws, bypass Parliament and adopt decrees on an unlimited basis. Journalists now face prosecution for spreading “false” or “distorted” information about the government and the virus, an offence punishable by up to five years in prison. Media reports have shown that media workers and sources at the health sector are starting to self-censor. UN human rights experts and human rights groups have voiced serious concern about the reforms.

- On 16th March, Honduras declared a state of emergency and suspended a range of constitutional rights, including freedom of expression. The UN High Commissioner for human rights in Honduras has expressed serious concerns about the measures, while the IACHR’s Special Rapporteur for freedom of expression has labelled them disproportionate.

- Draft legislation in Cambodia would empower Prime Minister Hun Sen to restrict all civil and political liberties, without time limit or safeguards. The executive could gain unlimited surveillance of telecommunications and the power to control media and social media. The bill comes amid a longstanding crackdown by the government on civil society, the media and the political opposition.

- On 31st March, Armenia’s parliament granted authorities broad surveillance powers, ostensibly to use mobile data to track the virus.

- South Africa recently passed regulations criminalising content intended to deceive any person about the pandemic or the government’s measures to address Covid-19.

- In Thailand emergency powers have been announced including criminal prohibitions on information about the virus that is deemed “false”, likely to “instigate fear” or is “intentionally distorted to mislead the public”.

- In Romania a decree has been introduced which allows the authorities to remove content and block websites where content provides “false information” regarding the evolution of COVID-19 and prevention measures, without the possibility to appeal against the decision.

Derogations from human rights obligations

To facilitate these actions, some states are also derogating from their obligations under regional and international human rights treaties.

As of April 2nd, eight countries have notified the Council of Europe of their intention to derogate from the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) under Article 15 (Albania, Armenia, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, Moldova, North Macedonia and Romania). Ten Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Panama, Peru) are derogating under the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR). Six of these states have also notified the UN about derogating from the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), see here.

Importantly, the ICCPR, ECHR and ACHR already provide for restrictions of human rights in the context of protecting public health and public order – provided that any restrictions are legal, necessary and proportionate. The right to liberty protected by Article 5 of the ECHR, for example, might be limited where it is necessary to compulsorily isolate certain persons. So too, the right to freedom of assembly, protected by Article 11 ECHR, may be limited by reason of the ongoing need to prohibit large gatherings. Such restrictions may be justified, provided they are temporary, time-limited, necessary, proportionate and subject to appropriate scrutiny.

As a result, it is not evident that the COVID-19 outbreak requires formal derogation from human rights treaties (see analysis by Martin Scheinin, former UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism and Professor Kanstantsin Dzehtsiarou, University of Liverpool).

Regardless, the UN Human Rights Committee has established that in the context of an emergency, derogations from human rights treaties must be of an “exceptional and temporary nature”. Further, they must be limited “to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation”. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights has referred to derogation measures in similar terms. Further, as the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has made clear, states must ensure that normal checks and balances of pluralistic democracies continue to operate during an emergency, especially in relation to freedom of expression, civil society and the media.

The need for critical journalism

As executive power expands around the world, critical journalism is more essential than ever. As a group of UN human rights experts recently emphasised, journalism may be most crucial during a public health emergency, particularly in relation to monitoring government action. In responding to the virus, governments must take steps to protect the work of journalists, not criminalise their efforts to provide essential information.

This will remain the case even when the pandemic eventually recedes. While governments might present emergency measures as short term and temporary, this is often not the case. The UN Special Rapporteur for human rights and counter terrorism, Fionnuala Ni Aolain has observed that emergency powers offer governments useful “short cuts” and therefore tend to “persist and become permanent”. In Egypt, for example, authorities have continuously extended the state of emergency declared in 2017 with harmful implications for human rights. Similar concerns have been voiced about intrusive surveillance measures recently established in some countries to track the virus. Critical investigation of all ongoing emergency measures is essential.

Media Defence strongly recognises the need to defend journalists and media outlets throughout this crisis and beyond it. We will continue to provide assistance through emergency legal support, strategic litigation and local capacity building.

If you are a journalist in need of legal support, please click here.

If you are a fact-checker in need of legal support, please visit this website.

For a Spanish version of this article please click here.

Recent News

Landmark Ruling: Kenya’s High Court Declares Colonial-era Subversion Laws Unconstitutional

Media Defence welcomes the verdict of the High Court in Nakuru, striking down sections of the Kenyan Penal Code which criminalise subversion, citing them as relics of colonial oppression that curtail freedom of expression. Justice Samwel Mohochi, delivering the judgment, asserted that these provisions were overly broad and vague, stifling dissent rather than serving any […]

UN Rapporteurs Call for Protection of Brazilian Journalist Schirlei Alves

UN Rapporteurs Call for Protection of Brazilian Journalist Schirlei Alves Amid Defamation Charges Stemming from Rape Trial Coverage A letter dispatched by UN rapporteurs to the Brazilian Government calls for protective measures for women journalists covering cases of sexual crimes. The letter also denounces the conviction of Brazilian investigative journalist and women’s rights defender, Schirlei […]

Convite à apresentação de candidaturas: Cirurgia de litígio em português na África Subsariana

Cirurgia de litígio em português na África Subsariana Aplique aqui 23 a 25 de julho de 2024 em Nairobi, Quénia Prazo: 3 de maio A Media Defence está a convidar advogados sediados na África Subsariana que falem português a candidatarem-se a participar numa próxima cirurgia de litígio sobre o direito à liberdade de expressão e […]