To celebrate our 15th anniversary, we look back at some of the cases we have worked on that have had positive outcomes for freedom of expression. To start with, we are highlighting the landmark MOVICE mural case, in which the Colombian Constitutional Court ruled in favour of justice and human rights.

The ‘false positives’ scandal and the MOVICE mural

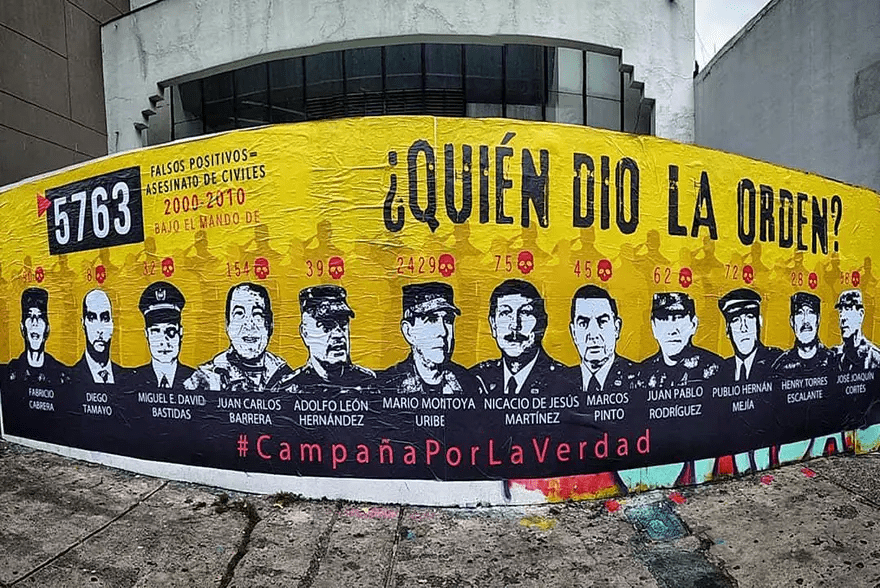

In October 2019, a group of activists gathered to paint a mural on a wall facing a major highway in central Bogotá. Organised by the Movement of Victims of State Crimes (MOVICE), the mural identified five high-ranking military officials who were in key positions during the extra-judicial killings of thousands of civilians, now referred to as ‘false positives’. Just hours later, members of the Colombian army painted over the artists’ work.

The ‘false positives’ scandal was first exposed in 2008. From the early 2000s, in pursuit of victory against the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), Colombian military commanders began to incentivise the killing of guerrilla combatants by offering rewards in exchange for higher body counts. Thousands of innocent civilians were consequently murdered and framed as guerilla soldiers. At the time the mural denounced the impunity of the false positives, no one had been charged in relation to these crimes. MOVICE sought to rectify this, emblazoning the question ‘Who gave the order?’ on the mural.

Although the military intervened before the activists could finish the artwork, their act of censorship proved counterproductive. Hours after its removal, the activist Puro Veneno collective shared the original design of the mural on social media along with the hashtag #EjercitoCensuraMural (#MilitaryCensorsMural). MOVICE also published photographs of the mural on social media, which quickly went viral. The image flooded the streets of Bogotá in a variety of new formats, from posters to face masks.

Street art in Colombia

Street art has long been a protected form of expression in Bogotá. It has become a key way for activists to disseminate their messages. In 2011, the municipal government decriminalised graffiti. It did this in response to a wave of protests that followed the murder of Diego Becerra, a 16-year-old street artist, at the hands of the police. In a manipulation chillingly reminiscent of the ‘false positives’ scandal, police had attempted to frame Becerra as a criminal by planting a gun at the scene of his death. The underpass where he was killed continues to be repainted by street artists, as not only a commemoration of his life, but also as a reminder of the crime committed by state agents.

This reflects the importance of street art in Bogotá as a method of challenging the state at crucial political flashpoints, and preserving the memory of victims. During the protests at the end of 2019, activists again deployed street art as a method of protest against the government. Whilst marching for improved access to education, 18-year-old Dilan Cruz was killed after being struck by a gas canister fired by police. His name and image quickly spread across the city, including in the form of stickers that read “Dilan Cruz. They serve as an alternative history to that of the Colombian state, for everyone to see and to never forget.”

Legal action against MOVICE

Not only did the army soldiers censor the mural, MOVICE soon found themselves facing legal action for publicising the mural across social media. One of the commanders depicted, Marcos Evangelista Pinto Lizarazo, filed a tutela seeking the removal of any image of the mural from online platforms because of the perceived damage to his reputation. Mario Montoya Uribe, a former commander of the National Army who also featured in the mural, soon followed suit.

In response to the legal action, MOVICE asserted that they had merely represented factual information that did not tarnish the reputations or violate the rights of Pinto and Montoya. They claimed that the mural should be protected by the right to freedom of expression. Moreover, MOVICE outlined the importance of publicising ‘the truth’ of what happened and who was responsible so that such crimes would ‘never be repeated’.

An order to remove the mural from the streets and social media

In February 2020, however, a local court ruled in favour of the military officers and ordered that the mural be removed from both the streets and social media. By this point, the mural had been shared thousands of times across multiple platforms.

Our intervention in the case

Media Defence intervened in the case later that year by filing an amicus curiae before the Constitutional Court of Colombia. In our brief we contended that the ‘false positives’ scandal was already a topic of national and international discussion. The Attorney General’s Office, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace and the International Criminal Court were all in the process of investigating the ‘false positives’ scandal. Additionally, serious human rights violations such as the extra-judicial killings of thousands of civilians were a matter of public interest that should receive greater protection.

In our intervention, we highlighted relevant case law from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights recognising the prevalence of the public interest and freedom of expression over the rights to a good name and honour.

The local court’s order to remove images of the mural from the internet would place an excessive and impossible burden on MOVICE. We also argued that such a measure would not conform to the principles of necessity and proportionality under international law.

We concluded that, in this case, ruling in favour of the reputation of the military officers over the rights to public interest information and freedom of expression would breach international human rights obligations.

The Constitutional Court ruling: freedom of expression wins

Almost two years after the legal procedures began, the Constitutional Court ultimately ruled in November 2021 that the mural represented a legitimate form of expression. It stated that, given the seriousness and the impact of the ‘false positives’ scandal on Colombian society, the mural and the information contained within it were evidently a public interest matter.

The Constitutional Court also found that it could not find in the mural a direct attribution of responsibility to the military officers. It concluded that MOVICE intended to spread the message that the victims of international crimes demanded to know the truth about the ‘false positives’. The Colombian Court held that the subject depicted in the mural was “a matter of obvious public interest […], related to the responsibilities of a person who exerted a command role in the National Army; it is not in any way unsubstantiated by the judicial investigations that are currently underway, and it does not result in vexatious or disproportionate statements”.

The Court also clarified that “the truth reconstructed through extrajudicial mechanisms reinforces its collective dimension, contributes to the construction of historical memory, and also vindicates its autonomous value for the victims. The public narratives made [by victims], in addition to representing a way of inclusion, restore their right to honour and allow their own truth to materialise”. Importantly, the Court concluded that in the instant case “censorship can result in the re-victimisation of those affected by the respective crimes.”

The mural repainted

That December, MOVICE activists repainted the mural. This time, they updated it to include new statistics: 6,402 victims of extrajudicial executions. Additionally, they depicted a ninth military commander who was previously not part of the mural.

This case raises important questions around the protection of the right to freedom of expression of journalists and organisations who act in defence of public interest. Journalists in Colombia face a myriad of threats for their reporting, including violence, intimidation, and kidnappings. In recent years there has been an increase in the use of judicial harassment to silence or threaten journalists, such as when plaintiffs seek retractions or the disclosure of sources.

In a country that is still reckoning with violent crimes committed during the decades-long civil war, the MOVICE case challenges to what extent the right to freedom of expression coexists with the rights of public officials to honour and reputation. The Constitutional Court’s judgment, in favour of freedom of expression activists denouncing impunity for serious crimes committed by the security forces, is a strong vindication for justice and truth.

Recent News

Landmark Ruling: Kenya’s High Court Declares Colonial-era Subversion Laws Unconstitutional

Media Defence welcomes the verdict of the High Court in Nakuru, striking down sections of the Kenyan Penal Code which criminalise subversion, citing them as relics of colonial oppression that curtail freedom of expression. Justice Samwel Mohochi, delivering the judgment, asserted that these provisions were overly broad and vague, stifling dissent rather than serving any […]

UN Rapporteurs Call for Protection of Brazilian Journalist Schirlei Alves

UN Rapporteurs Call for Protection of Brazilian Journalist Schirlei Alves Amid Defamation Charges Stemming from Rape Trial Coverage A letter dispatched by UN rapporteurs to the Brazilian Government calls for protective measures for women journalists covering cases of sexual crimes. The letter also denounces the conviction of Brazilian investigative journalist and women’s rights defender, Schirlei […]

Convite à apresentação de candidaturas: Cirurgia de litígio em português na África Subsariana

Cirurgia de litígio em português na África Subsariana Aplique aqui 23 a 25 de julho de 2024 em Nairobi, Quénia Prazo: 3 de maio A Media Defence está a convidar advogados sediados na África Subsariana que falem português a candidatarem-se a participar numa próxima cirurgia de litígio sobre o direito à liberdade de expressão e […]